Introduction

Papua New Guinea. You have heard of it before, but I’m guessing you would be hard pressed to name a single fact about it or even guess its rough location on a world map. A few words might come to mind, but not much else: remote, undeveloped, National Geographic. If I told you it was a gold-rich, war torn country in central Africa you might believe me, but that would be totally wrong. Possibly a small island country of the off South America’s Northern coast, plagued by drug running and a lack of jobs? No, also not the case. In reality, this country of 16 million people encompasses the Eastern half of Papua, a massive island just north of Australia. PNG’s closest version to fame would be its place in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, where it is featured for its utter lack of development. In fact, the inland portions of PNG were some of the last large swaths of land to be “discovered” by westerners – as late as the 1940s.

Today PNG is a grab bag of dichotomies. Massive stretches of untouched rainforests abruptly scarred by open pit mines that have sparked devastating ecological disasters. Incredible cultural diversity undermined by crime-ridden cities where you are urged to carry your bag across your chest. Self-sufficient rural living contrasted against massive unemployment and extreme cost of living in urban centers.

My wife, Natasha, and I spent nearly three weeks visiting PNG in May of 2012, and this is our story.

Planning

Let’s start out by saying that just conducting basic research on PNG and trying to put in place any sort of plan in advance is a trying exercise. Unless you want to pay a small fortune to the tight-knit cartel of PNG all-inclusive tour operators, costing well upwards of $1,000 per day per person, you are pretty much on your own. The only guidebook for the country is an outdated Lonely Planet. Attempting to send emails and make phone calls to hotelkeepers, local guides, embassies, and transport companies is a hit-or-miss activity that would frustrate even the most seasoned traveler. At least three quarters of all email we sent would bounce back as undeliverable – later we found that sometimes it is because the email address no longer exists, but often it is because of the intermittent internet access in the country.

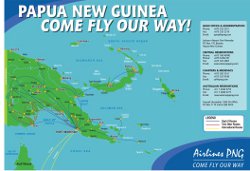

During one of our rest days in New Zealand, Natasha and I were able to finally sit down and book all of our travel into PNG as well as domestic flights to several main locations. Our reservations consisted of a patch blanket of carriers and times – painfully constructed over many hours of research. We spent way too much money and there was still one major hole in our itinerary – our last flight brought us to Wewak on the north side of PNG, but our flight on to Bali was out of Jayapura, a city on the Indonesian side of the island, about 200 miles away and requiring an international border crossing. “No problem,” I said. “We will figure it out. I googled some stories about people who have done this before. Plus, we can go to the Indonesian embassy in Australia so that we have visas in advance and won’t have to worry about that border crossing.”

Fast forward to a few days later. We arrive at the Indonesian Embassy in Sydney, seeking visas for our remote border crossing. “I am sorry sir, because of security concerns we are not issuing tourist visas for the Papua region. The border is closed, you will not be able to cross. Even if you could, it would take 1 week to get your visa.” We stood at the counter in a state of shock. Border closed? Security concerns? A week to get a visa? I questioned the veracity of these claims, but the consulate official wouldn’t budge.

My loving wife did not take this news well. Following many expletives directed at me and my ideas, the Indonesian consulate, and the country of Papua New Guinea, I was able to convince her that we should just give it a shot and figure it out while in PNG. I was going on fairly light evidence, a few stories I came across on the web (both several years old) and confirmation from a PNG travel agent that the border was “probably” open.

After working through the emotional rollercoaster set off by our visa fiasco, we had a weekend to spend in Sydney and had a lovely time. Sauntering through the avenues of picture-perfect Manly, I was beset with a pang of self doubt. Should we really leave all of this tomorrow and go to PNG for the next three weeks? Should we just cancel everything and enjoy strolls on the beach, pleasant weather, morning surfing, evening swims, and the overall pleasantry of this idyllic Sydney suburb? Why exactly would we want to trade this for all that we had read about PNG? Stifling humidity, crime-ridden towns, hungry mosquitoes, and utterly lacking tourist infrastructure (well, infrastructure in general). Reason and logic might suggest a change in plans, but there was no turning back now. The adventure was booked, and it was time to start make our way into PNG.

Getting There

The first leg from Sydney to Brisbane was a painless domestic flight. Our spirits were lifted having one flight down, as we knew that we had a close connection in Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea. From everything we had read, Port Moresby was not a place to spend much time. High crime, crumbling infrastructure, a dearth of tourism-worthy sites, and outrageously expensive hotel rooms. Our plan was to connect through the airport and never see the city.

In Brisbane, we transferred terminals and looked up to the big screens. “Port Moresby – Delayed.” Crap, shit, dammit. We aren’t even in PNG yet, and our trip was already getting screwed up. We did not want to spend the night in Moresby under any circumstances.

We paced through the Brisbane airport, trying to do whatever we could. We considered buying a new ticket on another airline – but that would have put us $750 out of pocket with no guarantee that we would make our connection. To make matters worse we had separate tickets for each leg of the flight, so the airlines had no obligation to make sure we made it to our final destination. We phoned the airline in PNG and asked if they would allow us to move through immigration quickly and help us onto the flight. They told us that if the flight from Brisbane landed early enough they would have someone there to help us. Also, she confirmed that we were checked in to the flight, so that our spots on the plane were being held. That gave us a slight sense of relief. We also managed to find an “Airlines PNG” representative in Brisbane who gave us a similar answer. The flight boarded about 90 minutes late. We sat anxiously on the plane, knowing that every wasted minute before takeoff was lowering our odds of making the connection.

The flight was a quick hop up the eastern coast of Australia, with a jaunt over the Coral Sea. As we approach Port Moresby the coral reefs were clearly visible from the air. Countless reef breaks make PNG a surfer’s paradise. We landed about 40 minutes before our next flight. Might just be enough time, we thought. We deplaned via air stairs, no fancy jet bridges in PNG, and were hit with the familiar yet feared blast of hot, humid tropical air. The first thing we noticed as we taxied to our gate was the number of decrepit planes littering the airfield. Some of them were literally being scrapped for parts right along the tarmac. It was an strange site, and certainly not something you would see at a "normal" capital city's airport.

There was no luxury of time to take in the sights and sounds, we rushed into the terminal and looked for the airline representative that was supposed to accelerate us through immigration so that we could make our connection. Nobody was around – anyone we asked just directed us to the long immigration line. Damn – this wasn’t going to be as easy as we hoped. We headed to the line with everyone else. Much to our dismay, another flight had landed just before us and the line was long – at least an hour wait. 35 minutes left. We decided to push on and not give up. We determined that people buying visas on arrival need to go to another line first, so we put on our most desperate look and asked people in line if we could go to the front and get our visas. Everyone sensed the urgency on our faces and let us move to the front. We paid for our totally over-priced visas and then made our way to the real immigration line. 25 minutes to go. We repeated the process and made our way to near the front of the line. Another gentleman in front of us had done the same thing. As he made it up to the immigration desk, there was a few sentences of back and forth chatter with the official. He then walked away from the counter and back into the crowd. He did not realize that he had to go to the other line first to buy his visa. He knew at that moment that his quest to make his own connection had been defeated. He would have to go back through both lines all over again. Poor guy.

22 minutes to go. We made our way to the immigration counter. “What is your purpose for coming to PNG?” “Tourism,” we responded. He issued a deep laugh and said with a mixture of humor and incredulity, ”Ha. Tourism.” Without much further study our passports were quickly stamped and we dashed off. 18 minutes left – WE MIGHT JUST MAKE IT. We ran from the international terminal to the domestic terminal (note: I am using the word “terminal” very loosely here. Basically just decrepit buildings with a few counters). The distance was further than we expected, but we got to the Airlines PNG counter with about 15 minutes before departure time. A few other westerners were standing around the corner. “We’re too late. They’ve closed the flight,” one of them said glumly to us in a thick Australian accent. "What? How is this possible? It’s a small plane, there are still 15 minutes left, and the airline said they would be waiting for us." I argued with the ladies behind the desk for a minute, pleading to get on the plane. They had no record that we were checked in, as the lady on the phone had promised, and simply said that the flight had been dispatched. It quickly became clear that this conversation was going nowhere.

That was it. We were stuck it Moresby for the night. Bloody hell. Totally screwed. I felt like I had been punched in the stomach.

As we stood around with the other westerners, we struck up a conversation with the Australian that initially shared the bad news. He had come in on the other flight and so he had one reservation going all the way from Australia to the Highlands. Because of that, the airline was obligated to put him, and all the others connecting from that flight, up in a hotel for the night. We explained to him that we were not so lucky since we had booked separate tickets. Even worse, we were told by an agent on the phone that we would have to buy new tickets if we missed our flight. Between the prospect of a $300+ hotel and $600+ to buy new tickets, this was becoming an expensive disaster to start our trip.

“Just stand in line with the rest of us as they rebook everyone and give out hotel vouchers. The airline is so dysfunctional they won’t even realize that you weren’t on the connecting flight.” Sure enough, we waited in the line and were given a voucher for transportation, meals, a hotel, and rebooked for a morning flight the next day. We were pretty nervous that at some point they were going to realize their mistake and leave us empty handed, but soon enough we were whisked away by the hotel van toward the Lamana Hotel.

Even before we left the airport grounds we were intrigued by the sights. Many hundreds of people were milling about just outside of the airport gates, many of them with faces pressed against the steel bars gazing into the terminal complex. “What are these people waiting for?” Natasha asked our driver. “Nothing, they are just hanging out. These people have no jobs and just find this to be an interesting place to spend the day.”

After about 10 minutes of driving, the van approached a set of huge walls 15+ feet high with large steel doors and a dozen armed security personnel. The “5-star” Lamana Hotel was protected like a fortress. We quickly learned that you need to apply a 2 star deduction to convert between western standards and PNG standards. The sprawling hotel had basic yet clean rooms and underpowered A/C to partly stem our profuse sweating. We even went to check out the pool, which was tiny and surrounded by concrete walls and barbed-wire fences. The Lamana had all the luxury you would expect in a prison yard.

Western Highlands

The next morning we made our way back to the airport, arriving more than 2 hours early for our 8:00am flight. We were not leaving anything to chance this time. We went up to the counter to check in, and of course they had no record of our missed connection and rebooking. We waited a while with some fellow travelers. There was a bit of anxiety that they would discover that we shouldn’t have been provided the hotel room and free rebooking, but alas the utter chaos worked in our favor and we eventually received our board passes. We boarded the surprisingly modern jet and made our way to the Western Highlands.

Our hotel keeper, Pym, met us at the airport. It was a good sign. We also met our guide, Wani, and our driver, Carowa. (As a side note, pretty much all names in PNG are awesome.) They picked us up in a dilapidated Land Cruiser. In fact, you could watch the road pass by through the large rusted-out holes in the bottom of the vehicle. The first thing that they pointed out to us on the drive was the pigs at the side of the road. They were always tied up to a stick thrust into the hard ground and topped with a flower. This was the sign that the pig was for sale. The possession of pigs in Papua New Guinea is a major status symbol. And I don’t say that lightly – it is a MAJOR status symbol. The pigs are gifted and eaten for very special occasions, such as a wedding or upon settling a major dispute. For this reason, pigs do not come cheap. The hogs on the side of the road ranged from $1,600 to $2,000. I’m no farmer, but that seemed awfully expensive for a hunk of pork in a third world country.

It was a 45 minute drive up to the mountain lodge, and we passed many sites typically encountered in the developing world: roadside markets, trash scattered about, locals jammed into buses and truck beds, and abhorrent road conditions (in some places worse than Los Angeles!). One of the highlights of the drive was passing a double marriage celebration, which consisted of a bunch of people crammed into the back of pickup truck. Two women, the brides, stood at the front of the truck bed dressed in their finest clothes and topped with possum fur hats.

The terrain was mountainous and spotted with small farms growing a wealth of fruits and vegetables. The Highlands produce staples such as corn, broccoli, oranges, tobacco, and tomatoes for the entirety of the country. While fresh produce is an expensive scarcity elsewhere in the country, it is in abundance here.

We made it to our cabin in the mountains and embraced the cool, dry air. The altitude creates respite from the suffocating humidity encountered in the rest of PNG. We settled into what would be our home for the next 3 days. There was one other couple staying there the first night, a German couple into diving and a flair for obscure travel (The man salivated as he described his dream trip of scuba diving under the ice in Antarctica.) We walked with them and our guides into the neighboring village to see their crops and learn a bit more about the local way of life. The variety of crops that the villagers were growing was incredible, as was the size of their tiny gardens. Every square of land in PNG is owned by someone, and in the villages most people have just a small plot to call their own. The land ownership structure reinforces the sustenance approach to farming to this day.

The next morning we decided to hike up to the top of Mt. Hagen, the namesake for the largest town in the Highlands and PNG’s second-tallest peak. At 12,000+ feet in height we knew that we had a long of day of hiking ahead (our cabin was situated at around 5,000 feet). We were assigned a local guide, Pancha, that knew his way up to the top and a student guide, James, who spoke some English and was in essence our translator. Our local guide showed up barefoot, clothed in ragged shorts and a woven shirt, and clutching a machete. He looked like the most rugged mountain man ever. Unfortunately for us he didn’t speak a word of English, so any question we wanted to ask him had to be funneled through James, whose English was fairly limited. The cook at our lodge provided Natasha and I with some sandwiches and fruit for lunch on the trail. The guides received a bag of dinner rolls.

For the next five hours we proceeded upwards. At first we marched through wet rainforest along a steep, muddy trail. At times we were using our hands and feet to climb up natural ladders of tree roots. It was slow progress. Along the way James pointed out large flowers. Each one had been strapped against a Y-shaped tree trunk. Among the tree trunk and the flower was all sorts of lashing, bent branches, etc. It was a bird trap. The bird would be attracted to the flower, and when it approached it would trigger the trap and snap the bird’s neck in between two sticks. The flower was still attached to the stem and was living, so the trap would be good for many weeks. Ingenious.

We stopped frequently to catch our breath and drink water. By “we” I mean me and Natasha. The guides moved quickly, never showed a drop of sweat or shortness of breath, and never took our offer for a sip of water. Their stamina was incredible. Once we made our way above tree line we stopped for lunch. Our local guide started piling some of the dry grasses together and then lit the heap on fire. Intrigued, we asked James what was going on. “The smoke signals that we are up here to the villagers down below.” Okay, I guess that might serve some use, but we were left a bit perplexed. We immediately gave our local guide the nickname: “Fireman.”

Once we were ready to starting hiking again the fire continued to burn and was spreading to the surrounding grass. “Shouldn’t we put that out?” Natasha and I asked. “No, it will eventually go out.” Okay, that goes against everything I ever learned as a Boy Scout, but I will leave it up to the locals. The wind shifted such that as we headed uphill the smoke was blowing into our path. We choked on the billowing white smoke as we climbed. We grumbled about the signal fire that was now burning our eyes and affecting our already-taxed lungs. “Why didn’t they put out that stupid fire?” we asked ourselves. The two guides didn’t seem affected as they hiked through the smoke, but we definitely were not enjoying it.

Eventually the fire did die down and we climbed out of the choking fumes. However the smoke was quickly replaced by clouds as we gained elevation, at times we walked right through the heavy mist that hugged the mountainside. The clouds were thick as we reached the summit, but we had a few minutes of good fortune where the sky broke free and we could see the surrounding landscape and Mt. Hagen town.

On the descent we clambered down the mountain cautiously, trying to minimize the number of times we fell on our asses in the slippery mud. In the forest we came across the first of many bird traps that we had seen on the way up. A small bird had been caught in the device, its neck snapped as it swooped in to eat from the flower used as bait. “Fireman” released the dead bird from the trap and held it in his mouth while he used a stick to reset the snare. With a smile on his face, Fireman put the bird in his pocket and we continued on. It would be his dinner. We asked James “is this Fireman’s trap?” “No,” he responded. James wasn’t particularly verbose, but we pried for more detail. “Well, is he allowed to take the bird if it is not his trap?” “Well, he is here so he should take it.” Not exactly the answer we were expecting to hear, but we learned later that the traps are semi-communal. If you come across an ensared bird and the landowner is not around, you can take it. However, you are expected to reset the trap.

We made it down the mountain and scarfed down a nice meal back at the lodge. Following dinner was an interesting demonstration of a traditional mating dance, where the men and women wear face paint and rubs their cheeks against one another. It was a bit gimmicky, but interesting. The Germans loved it and annoyingly took videos and flash photos of each moment.

We spent our remaining days in the Highlands experiencing more of the cultural aspect. On one of the days we had a different guide, Ice Man. I asked him how he got his nickname. “Not a nickname. I was born during an ice storm [extremely rare in PNG], and so my father named me after the memorable event.” Awesome.

We went to a neighboring village to visit the chief and his wife. It was a nice photo op to see a chief and his three wives in full traditional garb and hear some interesting stories translated by our guide. It was part tourist trap and part real. He is really the chief and these are his actual wives, but in reality they only would dress up like this 1 or 2 times a year for special events. One of the more interesting items was the chief’s spear. He explained that it was made from his father’s tibia (lower leg bone) and that he has killed 3 men with it. Sounded pretty bad ass, and I was in no position to doubt that assertion!

On the way back from the chief visit we passed Pym’s house, the owner of the lodge we were staying at. He had the only house in the surrounding area made with modern materials (sheet metal roof vs. thatched with leaves). Pym also had quite a collection of pigs. The guide and other people in the village noted Pym's wealth and power, always commenting on the quantity and size of the pigs: “He is a very powerful man, he has many big pigs.”

Making our rounds of the Highlands tourist hotspots, we went to go see a performance by the famed “mudmen." The story goes something like this:

A tribe in the highlands was attacked by a rival tribe and forced off of their land. The ousted tribe knew that they were outnumbered and could not take back their homeland in a straight on battle, so they came up with a plan. They went to a river bank that held a special gray colored clay. They rubbed their bodies in the clay to look ghostly white and also built masks that made them look like out-of-this-world creatures. Bamboo sticks were used on their fingers to give a wolverine-like appearance. They then crept back into their occupied village one evening and managed to convince the rival tribe that they had disturbed the spirits. Terrified of the “ghosts,” the rival tribe left the village immediately and everyone then lived happily ever after.

It was gimmicky, but we arrived just as a rainstorm was lifting, and so the misty air made the scene pretty surreal. While we were there we also met a local lady who was tending to an eagle she had trapped. She was keeping it as a pet until it was ready to be eaten. So weird.

The last notable stop we made was to the main market in Mt. Hagen town. The locals claim that this is the best market in all of PNG, and it definitely seems like that could be the case. The covered market is very well organized and has a fantastic array of fruits, vegetables, meat, and sewn goods. We particularly enjoyed seeing the live chickens that were sitting untethered on the vendor’s tables. The vendors had trained the chickens to sit patiently; we had never seen such a thing before. I tried finding a possum-trimmed beanie, but they were all sold out. Schucks.

Fly River

Our next destination took us to PNG’s most isolated district, the Western Province. Our plan was to connect up with the most well-known guide in the area and spend about five days exploring the rainforest along the tributaries of the Fly River. To get there, we first flew from the Hagen airport to the outpost town of Kiunga. The flight took us over an incredible expanse of untouched rainforest and was a reminder of how much wild, virgin territory remains in Papua New Guinea. Other than a few roads just outside of town, there were no signs of any development along the 208 mile flight path. Kiunga is a truly isolated town roughly 500 miles from the ocean by boat along the Fly River. The only road in the area is 85 miles of dirt that goes between Kiunga town and the Ok Tedi gold and copper mine. The mine is an interesting and sad story in itself:

Originally majority owned the by mega mining company know known as BHP Billiton, extraction from the open-pit mine on Mount Fubilan began in 1984. The mine location was so remote that an entire town, Tabubil, had to be built up from scratch to support it. Part of the original construction plan called for the creation of a “tailing dam” that allows water runoff from the mining operation to settle before it is allowed to enter the adjacent river. This is designed to minimize the particles that make it into the downstream rivers. However, during construction an earthquake destroyed the partially-built damn. To avoid incurring additional cost, they decided to not rebuild the damn and simply let the water flow directly into the river. This decision had a tremendous environmental impact, spilling 80 million tons of contaminated tailings, overburden, and mine-induced erosion to flow into the waterways each year. The impact on the environment is stark and the mighty Fly River is filling up with sediment. At this point, the river can barely accommodate boat traffic during the dry season. Without a massive dredging campaign, the towns of Kiunga and Tabubil will lose their primary supply line with the outside world.BHP exited the investment after acknowledging in 1999 that the project was the cause of "major environmental damage." Most of the gold has been extracted from the site, and the mine may close down altogether by 2015. Meanwhile, Mt Fubilan is a mountain no more, but merely a hole in the ground.

Upon landing we met up with our guide, Samuel “Birdman” Kepuknai. The first order of business was to find a place to stay in town for the first night before we started our trip up the river the following morning. We told Samuel that we were on a budget, so we skipped the $300 per night main “hotel” in town (which was not all that nice) and went to the more affordable option, which turned out to be a terrible, terrible guesthouse. Pretty much the worst place we have ever stayed, and to make it even worse it still cost us $100 per night! The bedroom itself was bad, but the bathroom and “kitchen” areas were really what made it awful. It looked like something from a horror movie. The view from our room was the neighboring bar where everyone just throws the empty cans out the window, leading to a mountain of empty beer cans.

After settling into the lovely room we went out to a nearby birdwatching spot to see the Birds of Paradise, a unique species of bird endemic to the island of New Guinea. We traveled several miles along the main road when our truck got a flat tire. Charlie, our driver immediately got to work as we tried to find a shady spot to do some opportunistic bird watching while we waited for the tire to get changed. After spending time in the relatively temperate weather in the Highlands, we were struggling with the hot and humid afternoon weather. Eventually the car was fixed, but because we stopped on a slightly uphill stretch of road we had to push the car so that it could make a u-turn and coast down the hill. Charlie explained that the truck was a “push start,” the ignition was busted, so he had to get the thing rolling and then jump start the motor by engaging the clutch!

We made our way a little further down the road to the intended bird watching spot. We spent hours looking for the birds and craning our necks to get a sight of them high in the branches. We could hear them but only had fleeting glances. After a while it became difficult to feign interest in looking for birds; I think Samuel was a bit surprised that we were not big time birders. Once the sun went down we cheered at the slight reduction in temperature and made our way back to town. We cooked some pasta at the guesthouse and chatted with the security guard, Lucas. I am not sure if he was mentally challenged, high on drugs, or what. Lucas was in his mid twenties and had a habit of giggling. He spoke some English, but seemed to have no ability to process what I was saying. He was fascinated with our camera and wanted to have a picture taken. As the evening went on Lucas kept telling me that I was his good friend. He said that if I ever visited his town he would kill a big pig for me. WOW, THAT’S A BIG DEAL. Since I had this new found friend, I asked if we could pay him to use his cell phone to make a phone call. He said he needed 5 kina (about $2.50) because that was the minimum amount that he could pay to top off his account. I gave him the 5 kina and he went to buy some credit for his phone so I could make the call. I made the phone call and checked how much credit was used – less than $0.40. That left him about $2 in credit on his phone. I was shocked at the total lack of restraint now that he had some credit on his phone. He spent the next 20 minutes texting and calling his friends until his extra credit ran out. At one point he even had us get on the phone with his girlfriend to prove that he was hanging out with Americans. When he realized that he was out of credits, he put his phone down and went back to the sheer boredom of his job as a security guard.

In the morning we woke up early to go see the birds again. This time we had some better views of the Birds of Paradise. They are truly incredible birds, known for their elaborate tail feathers and high-energy mating dances. The plan was to then rest back at the hotel for a bit before beginning our trip up the river. Just after 11 in the morning, Lucas came to our room to kick us out the guesthouse because “our time was up.” Even though no one else was staying in the guesthouse, my supposed “good friend” was making us leave just a few minutes after the check out time. This was the first time we have ever been kicked out of a hotel, and it was the worst place we have EVER stayed!

After waiting on the street for Samuel and Charlie to pick us up, we eventually got going out to the place to pick up the boat. On the way the truck got two more flat tires. Ridiculous. What kind of tires did Charlie have on this truck? And why were they are self-destructing during the two days we were using the vehicle? After fixing the flats and an additional hour of driving we reached the end of the road, a riverside village called Drimgas. We had to wait quite a while in Drimgas for Samuel to meet us with the boat. At first we kept to ourselves under a thatched roof, the village seemed very quiet. But overtime the kids of the village began to gather around us. We said hello and offered high fives, but the kids were quite skeptical. Eventually we started spelling out words in the dirt using a stick and a few kids could read it. They liked that game a lot and it got them warmed up to us. Then we took pictures and showed them on the screen of the digital camera. They thought it was hilarious. We then started a game where we asked kids their names and I would try to pronounce them. They thought that was even more hilarious. All of the names were very different from normal English words, so they would make me repeat some of the names over and over until my pronunciation became passable. Unfortunately all the fun stopped abruptly when some old guy came out and yelled at the kids. It turns out that they were supposed to go to church that day and skipped out, so he was not happy at all.

Charlie eventually turned back with the truck to go back to town. The bed of the truck the jam packed with people from Drimgas eager to get a ride into Kiunga. I could not believe how many people crammed in there. Ladies from the village then brought up baskets of fish and vegetables to be brought to town for sale in the market. The bed of the truck was nearly scrapping the ground there was so much weight in the back.

Samuel eventually showed up with the boat. His daughter was with him, she was supposed to go back to town in the truck that had already left. Whoops! Rather than stay in Drimgas, Samuel decided to take her with us three more hours up river with us all the way to our destination for the next two days, the small town of Drimsky.

We arrived in Drimsky just before dusk. High on the banks of the river, the small village has about 50 inhabitants. Our homestay arrangement was with our boatman’s family. The houses are built as one large room elevated about 10 feet off the ground. To accommodate us they built a “guestroom” inside his house for us by adding lightweight bamboo walls in one of the corners. It was the first time a westerner had stayed the night in their village. Samuel relayed that the grandma living with the family remarked that she “never thought she would see this happen in her lifetime.” It was pretty incredible sitting in their home, watching them make dinner over the fire burning in the corner, learning about their family, and getting a feel for village life in PNG.

Samuel then woke up at 4am to take his daughter all the way back to Kiunga town and then back to the village to meet us around lunchtime. Something like 8 hours on the boat, probably spending a fortune on fuel in the process. It all made no sense to us.

During the day we watched the family cutting down a palm tree to make sago. Sago is a staple in the diet of villagers in this region, but is not much to be desired if you are used to western food. The process to make this starchy food is incredibly labor intensive. First, they must cut down a mature sago palm tree. Then the bark is peeled off of a portion of the trunk, exposing the interior fibers. The villagers (well, mostly the women) then spend hours pulverizing the fibers with hand tools. Once the inside has been turned nearly to dust, the powder is carried to the river and placed in contraptions designed to hold the powder as it gets mixed with river water. The sago then condenses into a dough-like state and is stored in bags. The sago is then pan fried by families for every meal of the day. Eating sago can best described as the taste and texture of a flavorless, fermented giant gummy worm. During certain times of the year a certain flower called Pandanus blooms and it is used as a topping for the sago which makes it decidedly more palatable. Even after all this hard work, there is little glamor in the diet for the people of PNG. Living in a sustenance fashion, they have a survivalist “food is fuel” approach to diet. The concept of eating the exact same thing every day if hard to swallow for many of us, but it is an entirely normal concept in Drimsky and most of PNG.

The lowlight of our time in Drimsky was the wretched bathroom. We are both pretty experienced with “roughing it,” but this one was particularly rough. Tash could barely handle going into the tiny bamboo hut with a hole in the ground. The close encounter with countless flies, bees, and cockroaches made for a stomach churning experience.

During our days in the Fly region we spent lots of time checking out the amazing birdlife. In the wild we saw pygmy parrots, crowned pigeons, birds of paradise, and numerous other exotic species. One day we stayed at a lodge that had a resident Cassowary that was semi-tame. The massive bird would occasionally walk out of the forest and hang out near us. Part ostrich, part dinosaur in our opinion. We had fun trying to have photo shoots with the bird. The other wildlife encounter that was less fun had to be the leeches. After some heavy rains we hiked a lightly-used trail and were absolutely ambushed by leeches. The tiny creepy crawlers lunged at us by the thousands and were ever so eager to attach to our shoes, crawl up our legs, and dig in their teeth for a sip of blood. We had to stop every couple of yards to flick them off our shoes, clothes, and skin. For the next few days we were hyper-paranoid about leeches.

After returning to Kiunga town, we spent one last night back in our dismal guesthouse before departing. Walking into one of the markets we saw a sign on the window explaining that for the time being achohol was banned in Kiunga because of “the event.” We inquired with Samuel to get the full story: earlier in the month people got drunk after a soccer game and then started looting the Chinese-owned shops in town. They ransacked several shops and then tried to start prying open shipping containers in the port area. The mayhem settled down after a day, but additional police were brought in to ensure peace and the local government decided to ban alcohol. This was all somewhat good news for us, because it meant that the beer-can-mountain bar next to us would not be keeping us up at night.

Sepik River

We landed in the northern coastal city of Wewak with limited time and no plan (i.e., the worst way to travel in PNG). Our first priority was to determine our options for getting to Vanimo, the border town from which we would leave PNG for Indonesia several days later. We went to all the airline desks in the airport with no luck; none of the flights were leaving on a day that was early enough to guarantee that we could get our visas in time for our flight on to Bali. We then hopped on a shared van (their version of a bus) that took us into town for about $0.50 per person. When we got into town the guys working on the van asked where we were going and offered to escort us through town for our safety. When we declined they suggested that we keep our bags on our chests and hold onto them tight. It was nice of them to offer, but not exactly the best introduction to Wewak. In town we asked about ferry options to Wewak, but we could not get a straight answer and it did not seem like the timing would work. Options by road also seemed sketchy, half the people we asked said “no problem, there are multiple Land Cruisers doing the drive every day.” Meanwhile the other half was more pessimistic, “the Land Cruisers only leave when there is enough people, and the road is in very bad condition because of the rains.” In the end we put our names on the waitlist for an Air Niugini flight that would leave on Wednesday, just two days before we had to catch a flight from Jayapure to Bali. The flight was expensive, not guaranteed since we had no seat assignment, and arriving in Wewak a day later than we had hoped, but it was the best option we had. We headed back to our airport hotel a bit dejected but knew that we had a Sepik trip to plan.

At a hotel across from the airport, we found a guy that leads tours to the Sepik. His name was Alois and was one of the more established tour operators in the area. He admitted freely to us, “my all-inclusive tours are very costly,” but he was willing to put us in touch with a local guide so that we could construct a piecemeal tour that was more within the realm of reason. Fortunately for us, Alois had a truck leaving that night.

We killed time by wandering around town and then hung at the beachside hotel after dark, waiting for our 11p departure towards the Sepik. The truck ride out to the boats leaves in the middle of the night, so that you arrive about an hour or two before dawn. The trucks then pickup Sepik villagers who want to take their good to market back in town. The open-sided truck was loaded with goods, and we each had a section of bench to lie on. Let’s just say with was a rough night. The truck bounced around on the rough roads, slammed on the brakes when meeting cars coming from the other direction, and kicked up endless amounts of dust.

After 5-6 hours on the truck we finally made it to the small trading post where the boats are loaded. It was total chaos. Trucks parked everywhere. Long boats, some fiberglass, some dugout canoes, were tied up many levels deep on the shore. I watched over and over as hundreds of pounds of goods were offloaded from a truck onto the ground near the truck, then moved again somewhere closer to the boats, then moved again to another pile when the boat was moved, and then finally onto the boat itself. Similar piles were built and moved for goods coming off of the boats and destined for the trucks. As a management consultant, I would describe it as a disaster in the practice of logistics.

Meanwhile, we waited while our boat was identified and eventually loaded with goods. Exhausted and frustrated at the chaos, we were relieved when the boat finally fired up its outboard motor and began to move, nearly two hours after our truck had arrived. Much to our chagrin, we soon learned that we would be making a stop on the other side of the river. The main shop and market is located on the other side of the river from the trading post, so the first stop came after a short 5 minutes of boat travel. We waited again for nearly an hour. Hurry up and wait. Near delirious from the lack of sleep, we were not in the mood for further delays.

We eventually headed up river on the heavily loaded dugout canoe. It was quite a feeling to sit below the waterline and cruise up the Sepik with the locals. The river was peppered with small villages every mile or two. We stopped occasionally to drop off passengers and goods. After about 4 hours we made it to our final destination, a small village in the “Blackwater Lakes.”

We spent the next few days cruising the Sepik and its tributaries in the dugout canoe and hopping from village to village. We found the linguistics diversity astonishing. Most everyone speaks tok pidgin today, the language spoken across PNG, but in some place villages just a few miles apart had local languages that were distinctly different. Another interesting part of the Sepik was learning more about the haus tambaran (“spirit house”) traditions and visting many such houses along the riverbanks. In many parts of the Sepik, the spirit house serves as the cultural and spiritual center of each village. A large, open-air structure, it is ornately decorated on the inside with wood carvings and drums made from tree trunks. Celebrations and special events are reserved for men only. In some cases the men even build a fence around the spirit house to keep the women out.

We arrived at the one village to the sound of beating drums and singing. Our guide exclaimed, “We are lucky, there is something going on today in the spirit house.” As we walked into the forested village the sounds grew louder and our anticipation grew. Our guide went ahead of us into the spirit house to chat with some elders and see what the situation was. Soon we were invited inside and welcomed by the group. Natasha was allowed in because she was a Westerner; there were no other women inside. A group of about thirty men were scattered about the area, some beating drums, some butchering a pig outside, some preparing the wood stove. It took a bit of explaining, but we eventually figured out the purposed of this event: a local man in the village had been caught taking his dead father’s name in vain. This may sound like no big deal to you, but it was considered a serious offense in the community. In order to make retribution, the man had to go into the forest, hunt a wild pig, and then bring it back for the men of the village to eat.

At the next village we came across another very unique event. The whole village, men and women, were gathered in the main dirt square of the town. There was a celebratory atmosphere in the air. Everyone looked quite normal, expect for one man who was covered in dry clay. From head to toe he was caked in a heavy gray muck. Hair, clothes, everything. Our guide explained that the man looked this way because he is working to resolve a dispute with his son. We were not sure of all the details in this case, but guessed that the mud signals to the village that he has an unresolved dispute (a sort of public shaming) and also brings a sense of humility to the two parties when they are negotiating face to face.

After visting several villages, we were suprised by a couple of things. First off was the utter lack of education and public health facilities. Most villages had some sort of school building, but we never saw class in session. And that's not just in the Sepik, but over the course of our whole trip. There was always some sort of story about a lack of funding, a teacher that got sick, waiting for a new teacher to arrive, etc. We also noticed extremely high incidence of normally rare syndromes and genetic disorders, including a textbook case of acromegaly, which is related to gigantism. This is due to both lack of healthcare as well as inbreeding (given propensity to find a mate within a small population, basically one's own village and possibly a few surrounding villages).

Our lodging in the Sepik was a simple affair. A family-run guesthouse of the most basic type. One large room, elevated on stilts, with bamboo dividers used to create a number of small rooms for guests. It was clear that this place was built with grand ambitions, but I don’t think that they received many visitors. The guesthouse owner explained at length one evening how dried fish was like their form of refrigeration. They could leave the fish over the smoke of a fire at it would stay good for a while. Up to several months, he claimed.

Another tradition that is beginning to die out in the Sepik is the “coming of age” tattoo. These tattoos are actually scars, cut into youth when they are deemed ready for manhood or womanhood. Each village has a different take on the tradition, some with cuts on the front, some cut the back to make it look like alligator skin. The tradition was less frequently applied to women, but when done was usually applied to the belly, such that the tattoo was accentuated when the women was pregnant. Early missionaries abhorred the practice and have been trying to stop the tradition since first contact. It is mostly abolished these days, although our guide mentioned that it is still practice in some of the most remote villages.

For our last day in the region we stayed at our guide’s house, along with his three wives and nine daughters. We were in awe as he talked very matter-of-factly about his family life. He has picked up a new wife about every 10 years. They all live in the same house, each claims one corner in the cooking house as her own. Three wood stoves, three sets of pots and pans. He explained with sadness that his only son had died some years prior. Our guess was that the plethora of wives and daughters was evidence of his quest to produce another son.

We ended our time in the Sepik with a brutal commute back to Wewak. It started with a 1:00a boat ride down the river back to the road. We made many stops along the way and had to wait in one village for 30 minutes because one of the intended passengers, the pastor, had slept through his alarm and needed to be fetched from his home. We made it to the trading post hours before dawn, hanging out in the boat as soft rain fell steadily. As more boats arrived and the trucks began to lumber up the road, we again got to witness the logistical quagmire to get all the boats and trucks reloaded. We then wrapped things up with an awful truck ride back to Wewak. The truck was packed, with Tash and I positioned next to several oil barrels. We were super tired, but the bumpy roads and cramped space meant that there was no opportunity to sleep. When it was dry out we would get covered in dust, when we passed through rain showers we would have to roll down the plastic covers and then deal with the stinky, dank air. There was a big sense of relief getting back into town, but we knew we still had to find a way onto our next destination.

Departure

As soon as we got back to Wewak it was a mad scramble to figure out a way to Vanimo, the town where we could go by land from PNG to Indonesia. The scheduled cargo ferry that we heard about had been delayed a week - so that was no longer an option. Meanwhile, the road was supposedly in bad shape because of recent rains. We heard a story about tractors having to pull Land Cruisers through one of the rivers that the road crosses. One of the Land Cruisers got flipped by the current. All people were able to escape safely, but everyone’s belonging were swept into the river and were lost. That turned us off of the road option. While we were looking at options a guy came up and offered to take us by boat for $750. It was somewhat appealing, but the prospect of 5 hours traveling in the open ocean in a small aluminum power boat also didn’t seem that safe. Frustrated, we ended up biting the bullet and paying for two expensive plan tickets that would leave in the afternoon the next day.

We were sick of spending money, but it was really our only chance at making progress towards the border. We showed up to the airport the following afternoon, hoping we would arrive early enough to atleast submit our visa forms. That turned out to be a total pipe dream. The flight went from being on time, to delayed, to cancelled and rescheduled for the next day. This was bad, real bad. We just went from having a connection that was too close for comfort to one that would be basically impossible for us to get across the border in time to make our flight. There was no way that we could get to Vanimo in time to get visas, cross the border, and make our flight to Bali. Fortunately, Air Niugini had to put us up in a hotel and pay for meals because of the cancelled flight. Unfortunately, the food at the hotel sucked even more than usual. We went to bed hungry and so, so eager to get out of PNG.

While a the hotel, we did have a chance to talk to some PNG locals who had also been affected by the delayed flight. One really refreshing thing about most all of our conversations with people from PNG was how free they felt to talk about what was happening in the country, both the good and the bad. There seemed to be broad consensus about the corruption among goverment officials, lack of funding for education and healthcare, and the need for more jobs. The fact that people were knowledgable about these issues and free to discuss them was definitely a good sign that change is possible in PNG.

The next day we waited for our flight to depart for Vanimo, we had some hope that they would leave early in the morning and give us some chance to get visas same day, but that didn’t pan out. We had to wait until 3p for the flight to leave. It felt like an eternity. Until the wheels were actually off the ground, we were nervous as to whether the flight would leave at all. We landed in Vanimo and dashed to the Indonesia embassy to see if we could put our visa applications in. We were about an hour late and the guards had no interest in cutting us some slack. We would have to spend the night in Vanimo and get our visas the next morning.

The next morning we waiting in front of the embassy gates, filled out the forms as soon as they opened, and paced nervously on the compound while we waited for them to deliver our visas, which eventually came around noon. We raced to the central market to catch the next van to the border. We were lucky to find a near full van in the market, and had to wait for a few more people to jump in so we could get going. The road meandered though virgin rainforest towards the Indonesian border. A lovely drive on a decent road, but we really were not in the mood for sightseeing. We were on a mission – to get across the border and off the island of Papua as soon as possible. The van stopped at a military checkpoint a few miles before the border where we had to get out to receive our passport exit stamps. The army guys were very well spoken in English and pretty entertaining, complaining that there is no immigration people stationed out there and they have to do two jobs but only get one salary. It was a bit hard to buy the “two job” argument, though. It did not seem like all that hard of a job given that only a few cars pass by each day.

With little fanfare we made it to the Indonesia border crossing and eagerly provided our passports to the Indonesian officials. Without much fuss they stamped us into the country and we proceeded to go find a taxi that would take us to the airport, knowing that we would have to figure out a way to Bali. Our originally scheduled flight had left hours earlier. As expected, there were no more flights to Bali that day and we would have to spend a night in Jayapura. We were quite fortunate to have found a helpful guy with the airlines that got us rebooked the next day for a relatively modest amount. We spend the evening walking around Jayapura, taking in the sights. The level of modernism, commerce, safety, and affordability was astonishing compared to what we saw in PNG. Most of all we enjoyed the cheap, tasty food. Without much hassle we found nice accommodations for a fair price, and I got a cheap haircut for a $1.50. We slept well knowing we had made it into, across, and out of PNG in one piece. An adventure, indeed.

Closing Thoughts

Let's just say that PNG is not for everyone. We had some incredible memories from our travels, but we put up with a lot of shit (sometimes literally) and paid of lot of money along the way. For particularly types of travelers I would say "go for it!", but just be mentally prepared for what's ahead. For everyone else, it is probably better to just enjoy the stories and pictures from a distance.

Would we go back? It is good question that we get asked frequently. I would say yes, but only under the context that we are not there as pure tourists, but rather involved in some sort of activity to improve the welfare of the local population. And there is plently of opportunity for improvement.

Copyright © 2013 by Kieran Culligan and Natasha LaBelle. All rights reserved.